A Great Ball in 1897

![]()

"At the Duchess of Devonshire's historic ball at Devonshire House last week, a photographic studio formed part of the arrangements, and we read that a camera was much in request to record some of the wonderfully accurate costumes worn by the guests. These included the creme de la creme of Society, from Royalty downwards, and some of the most celebrated men and women of history were personified. A photographic record of the scene and those who took part in it was no doubt secured, and in future times, when the doings of this great year are calmly narrated in calm prose, its interest will be extremely deep." Photographic News, 9 July 1897 |

![]()

Background to the Devonshire House Ball

Devonshire House – history and site

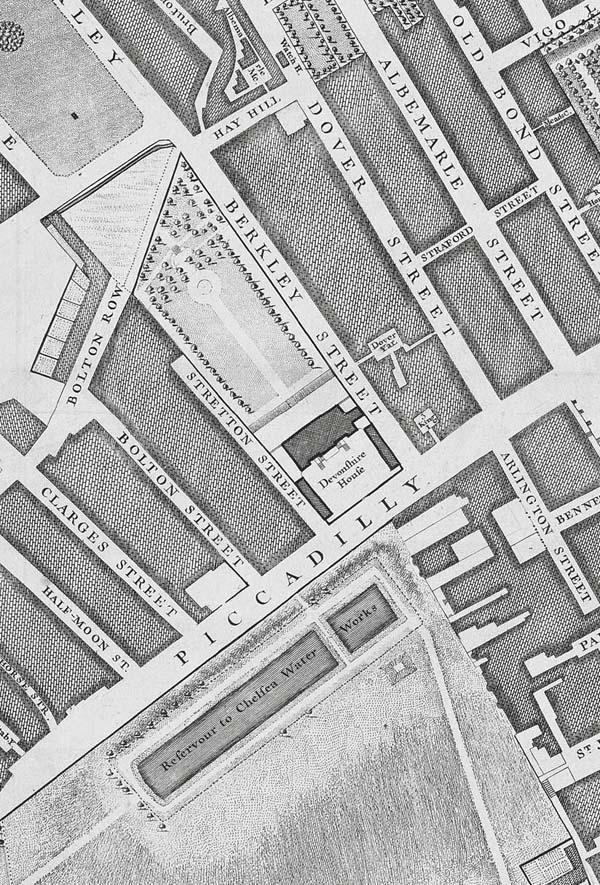

Devonshire House, was situated on Piccadilly, one of London's most fashionable sites with a view down across Green Park to Buckingham Palace and with a huge landscaped garden behind which stretched all the way up to the current Berkeley Square. This residence stood on the site of the former Hay Hill Farm and in the 17th century it would have been possible to look to the east and see the windmill, whose location is still marked in Soho by the name Great Windmill Street.

This land was acquired by Lord Berkeley of Stratton who commissioned the architect Hugh May to start work on Berkeley House in 1665, a project which, according to the diarist Evelyn, cost him almost £30,000. The exterior of this most strategically located of London residences consisted of a corps de logis flanked by service wings, was of plain unclad brickwork and it was shielded from the street by a high brick wall. Years of London smoke had made the external brickwork grimy, giving passers-by the impression that it was "cheerless and unsocial by day, and terrible by night…"

However, the exterior hid some of the most imposing interiors of any of London's grand houses and its collection of paintings was much praised. By this time of her life, Queen Victoria had been a black-clad and gloomy widow for 36 years, cheerless at her children's weddings and fiercely critical in her private journal of almost everyone around her. Sometimes she was not always too popular with other royalties, and Grand Duchess Olga of Russia remembered her father, the Tsar, referring to her as "that nasty, interfering old woman."

To many a common man, however, the Queen-Empress loomed large as a dear woman who had steered the empire to a hitherto unimaginable size – throughout the whole of which her jubilee would be celebrated in a myriad ways. Statues were erected, street parties held, tea parties, balls and civic events were organised throughout the empire, songs and poems composed for the occasion, and of course a whole industry of Diamond Jubilee souvenir item manufacture sprang up.

At the time of the Ball, Devonshire House was almost invisible from Piccadilly at street level, screened as it was from pedestrians by the high brick wall and plain wooden gateway. The historian JH Jesse was rather scathing about the merits of the mansion: "except during the brief period when the beautiful Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, held her court within its walls… little interest attaches to the present edifice."

The Duchess Dreams up a Ball

Louisa, Duchess of Devonshire (1832-1911) was one of London's foremost political hostesses, and as such, when word got around that she was planning a costume ball to celebrate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee on 2 July 1897, there was no attempt by other London hostesses to hold a competing event. Instead, they invested all their efforts into ensuring that they were on the guest list.

As the respected mother of the nation, Queen Victoria's sixtieth anniversary on the throne along with her title as Empress of India (of recent vintage), her jubilee was celebrated, in the press at least, with a feeling of exhilaration and respect tinged with hysteria. In order to commemorate the Duchess of Devonshire's much anticipated costume ball, the London photographic firm of Lafayette, who had ten years previously been awarded a Royal Warrant, was invited by the Duke of Devonshire to set up a tent in the garden behind the house to photograph the guests in costume during the Ball. This would have been a formidable commission for James Stack Lauder, the owner of the firm, and evidence from the extant negatives shows that he had transported from the Bond Street studio a variety of backdrops and props and, of course, photographic equipment.

In an interview with St James's Budget the following year Mr. Lafayette, acknowledging that he had been kept very busy since he opened a studio in London, described how he photographed the guests at the Devonshire House Ball: "I created a temporary studio in the garden, with a powerful installation of electric light; and though it may sound immodest to say so, the appearance of 'a gay photographer' at such a function was considered highly original, and was openly spoken of as a feature of the historic occasion.

"Lafayette's remit was to photograph guests who would be in costumes ranging from mythological and ancient Greek down to renaissance and oriental characters, and in order to capture the sense of event and location, the studio prepared a new backdrop (a painted canvas stretched on a wooden frame) which represented the lawn and gardens of Devonshire House complete with statuary. In the event of guests desiring a different background, the studio also transported its baronial hall and country estate backdrops as well as some studio balustrade, a piece of wall and a Turkish carpet.

More than 700 invitations to the Ball were sent out a month before the event – although reports of the event stated numbers up to 3,000 – which led to a rush of aristocratic women studying portraits and engravings of ladies "robed for coronation or beheading" in London museums and in turn there ensued an almighty battle to gain the time of the best dressmakers, wigmakers, theatrical costumiers and even metal-workers in London and Paris. Even though the concept of a career, and particularly a career on stage, was anathema to the British upper classes, it had long been acceptable for woman specifically to perform (usually singing) in front of a select audience provided the event was for charity. Princess Daisy of Pless in particular was renowned for her fine voice. Additionally, dressing up in historical costume to present a tableau vivant was a popular and respectable amusement and means of shedding some of the period's cast-iron inhibitions - even at the sullen court of Queen Victoria.

Costumes for the Ball

Many of those invited to the Ball spent fortunes on their costumes which in almost all cases were worn only for this event. The couturier Jean Worth of Paris wrote of a number of freak orders taken by his establishment, for which each pearl and diamond was sewn on by hand. One piece of jewelled embroidery "kept several girls busy for almost a month," and he claimed that the most expensive costume cost 5,000 francs. On the other hand, it should be remembered that then, as now, some aristocratic ladies and wives of the industrial barons had almost unlimited funds to spend on their clothing.

The fashion industry had reached an almost hysterical point in its development, and the new range of illustrated newspapers – aimed in the main at the female readership – was brimming with fashion plates, acres of descriptive text, gossip columns and detailed accounts of who was wearing what and where. At a time when ladies of distinction could not dream of dressing themselves without help from ladies' maids, and moreover would have been incapable of doing so on their own due to the immense complication of their sartorial confections encumbered by buttons and fastenings in unreachable places, an invitation to this greatest of Victorian costume balls would most probably have been received in most feminine quarters with great glee and provided the 'great ladies' of the land an opportunity to rise to a challenge.

The absurdities of feminine costume of the period, which are apparent to a modern reader skimming the pages of the illustrated press of the time, and the extremes of complication and fussiness had been gently lampooned – albeit with a masculine subject, some twenty years earlier by Edward Lear in his poem The Quangle Wangle's Hat c. 1875: "For his hat was a hundred and two feet wide, With ribbons and bibbons on every side, And bells, and buttons, and loops, and lace, So that nobody ever could see the face."

The Duchess of Devonshire instructed her guests to dress around the theme of certain courts, both mythical and temporal. They were to form various processions and perform a quadrille - for which many people practised for weeks. While some guests took their instructions literally, others modelled themselves upon paintings, and thus fell into more amorphous costume groupings, such as "17th century" or "Venetians." The habit of dressing up for private entertainments was masterfully parodied in Cecil Beaton's 1939 work My Royal Past by Baroness von Bülop – a mock autobiography in which he spoofs beautifully the spirit of the upper classes' love of masquerade with his sketch entitled 'A merry revel en travéstie'.

An Incipient Green Movement

In 1891 the publication of the pamphlet The Osprey, or Egrets and Aigrettes. Leaflet no 1: Destruction of Ornamental Plumaged Birds, by William Henry Hudson (1841-1922), the great ornithologist and founding member of the RSPB, was slowly raising the public’s consciousness regarding dame fashion’s hitherto wanton disregard for the bird question. Egrets in their millions were being killed in Venezuela and elsewhere to supply the feather trade and Hudson’s campaign was raising a few society ladies’ hackles. Even Country Life fairly fumed on the subject of unthinking vanity:

“no woman, speaking broadly, would put a bird’s feather into her hat, into her hair, or wear it for her personal adornment in any manner, if she thought that by so wearing it she was making it likely that another bird of the species would suffer; still less if she thought that the bird that had yielded her this particular feather had suffered in any other wise than that of a speedy and painless death to give her the plumage.”

The writer, rounds up his sermon on pain-inflicting fashion accessories by a call for a commercial boycott of these products and a biblical-sounding aide-memoir for those ladies still empty-headed enough not to understand the moral argument:

“Those things that are killed at once may be plucked, and their feathers stuck about according to woman’s fancy, or even be planted bodily on the head, with far less offence, but the plucking of the live thing is an abominable torture – if woman would but think!”

The notorious case of Mary Anne Walkley and conditions in the millinery trade

Social conscience had been stirred almost three decades earlier by the case of a girl from the millinery trade. In 1863 the 20-year old Mary Anne Walkley who was so overworked in conditions so awful, and yet apparently common in the millinery trade, that a letter writer in The Times claimed that “death has freed her from worse than Egyptian bondage.” Marx, in his Das Kapital, retold the sad story of this young girl who worked for Madame Elise (Mrs Wootton Isaacson) who was the first employer of the impoverished Rachel Gurney, later Countess of Dudley just a few years after this case broke into the news:

“This girl [Mary Anne Walkley] worked, on an average, 16½ hours, during the season often 30 hours, without a break, whilst her failing labour-power was revived by occasional supplies of sherry, port, or coffee. It was just now the height of the season. It was necessary to conjure up in the twinkling of an eye the gorgeous dresses for the noble ladies bidden to the ball in honour of the newly-imported Princess of Wales. Mary Anne Walkley had worked without intermission for 26 hours, with 60 other girls, 30 in one room, that only afforded 1/3 of the cubic feet of air required for them.

At night, they slept in pairs in one of the stifling holes into which the bedroom was divided by partitions of board. And this was one of the best millinery establishments in London. Mary Anne Walkley fell ill on the Friday, died on Sunday, without, to the astonishment of Madame Elise, having previously completed the work in hand. The doctor, Mr. Keys, called too late to the death-bed, duly bore witness before the coroner's jury that “Mary Anne Walkley had died from long hours of work in an over-crowded work-room, and a too small and badly ventilated bedroom.””

Marx apostrophised his retelling of the narrative with a quote from The Morning Star newspaper about “our white slaves, who are toiled into the grave, [and] for the most part silently pine and die."

An even earlier attempt had been made to raise women's consciousness or to prick their consciences about the ramifications of their desire for all things fashionable.The Lady's Dream by Thomas Hood (1799-1845) spoke of the eponymous Lady having an uncomfortable dream about the 'maidens young… with figures drooping and spectres thin' who worked 18 hours a day and lived in absolutely miserable conditions to produce the outrageously wasteful, obscenely impractical and visually gorgeous confections worn by ladies of society, and of the increased pressure during the Season:

| For the pomp and pleasure of Pride, We toil like Afric slaves, And only to earn a home at last, Where yonder cypress waves;'-- And then they pointed-- I never saw A ground so full of graves! |

Fortunately Thomas Hood's dreaming lady becomes aware of the dark underbelly of the fashion industry and, although in sleep, she learns the lesson that "evil is wrought by want of Thought, As well as want of Heart!"

Conditions in the millinery trade in the 1890s were no longer as abject those described by Hood taken up by Marx, but the commissions engendered by the forthcoming Devonshire House Ball markedly increased the general crush of costume orders for levées, drawing rooms, presentations, balls and weddings. Lady Violet Greville, writing of the Ball in The Graphic, echoed the sentiments of Andrea Chénier (In cotanta miseria la patrizia prole che fa?) when she deemed it newsworthy to mention that

"a sermon on the iniquity of spending so much money on clothes was duly preached in a fashionable church…the embroideries, as perfect as the need could produce, were many of them made in the distressful country of Ireland… dressmakers and costumiers were for weeks before nearly driven off their heads with work and anxiety… hairdressers distractedly rushed to and fro with tongs and hairpins for twenty-four hours consecutively… some of the costumes cost 1,000/., and…the jewels amounted to several millions."

A photograph by Russell & Sons of Baker Street, published in The Sketch on 3 November 1897, gives an idea of acceptable conditions in the workshop of Charles H. Fox, Theatrical, Historical & Private Wig Maker and Costumier, 25 Russell Street, Covent Garden, London W.C.

Intriguingly, Madame Elise came out of this whole episode with her reputation unscathed. The Huddersfield Daily Chronicle reported in 1891 that “the making of the gown to be worn by Princess Mary of Teck upon the occasion of her marriage with the Duke of Clarence and Avondale has been entrusted to the hands of Madame Elise and Co., of London, who have prepared and submitted a design for approval…” And, in jingoistic mode, echoed 56 years later at the wedding of Princess Elizabeth to Prince Philip of Greece, the same newspaper reported that “it is understood that the wedding dress of the Princess will not embrace a single article which is not of English manufacture…”

The workshop of Charles H. Fox, Theatrical, Historical & Private Wig Maker and Costumier, 25 Russell Street, Covent Garden, London W.C. |

The Ball and the photographer's tent

Guests at the Ball fell into two distinct groups, obliged to ignore each other's' shortcomings for the sake of form. The majority of the aristocracy were rigidly respectable and conservative in outlook whereas the behaviour of the circle around the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) was so "fast" or disreputable that Queen Victoria wished to have nothing to do with "Society". Memoirs of the time reveal the frenetic bedroom-swapping activities that took place in the great country houses where a gentleman was expected to be back in his own bed by 4:30 a.m. - just before the servants set about their first daily duties.

As the royal residences could not be given over to this sort of activity, Edward spent much of his time progressing around the country and visiting the stately homes and palaces of his friends where, as part of the entertainments, a good day's game shooting was proved to give the libido a visceral uplift for both the men and women. Among the images seen here, Daisy of Warwick, Daisy of Pless and Mrs Jamesare known to have been good friends with the Prince of Wales, who while being one of history's greatest royal philanderers also enjoyed the sheer company of beautiful women even if there were no sexual thrills involved. His wife, Alexandra, turned a blind eye and a deaf ear to his wanderings and absorbed herself with her children who almost worshipped her.

There is no accounting as to why only certain guests were photographed during the Ball in a tent erected by Lafayette in the gardens, but it can be assumed that, due to the complexity of their costumes and the complicated procedure of replacing the glass plate negatives in the camera, there simply was not enough time to capture all the guests. In a newspaper interview the following years, James Lafayette claimed to have photographed 200 sitters in four and a half hours – a staggering speed of 1 minute 21 seconds per photograph! Black & White claimed that "he photographed up to five in the morning, when the [camera-]operators had to abandon their task from sheer fatigue."

Additionally, perhaps not all the male guests were keen to be memorialised looking like a "tomfool" – as the Hon Reginald Baliol Brett (later 2nd Viscount Esher) complained in his diary! In an interview for The Lady's Realm three years after the Ball, Lafayette claimed to have photographed "no less than fourteen Royalties, who seemed to prefer the fun of having their photographs taken to dancing."

The suite of rooms inside Devonshire House which was emptied of its furniture for the Ball. |

There was huge press excitement surrounding the Ball, and crowds thronged Piccadilly on the night to watch the illustrious and heavily bejewelled and fantastically-costumed guests arriving in their carriages to spend the evening either in the magnificent ball-room hung with its old masters, or, as The London Standard informed its readers:

"Many of the guests were tempted to leave the supper-room for the garden, which stretches far back from Piccadilly. In the centre of the lawn shone an eight-point star, flanked by smaller stars at each corner, with the monogram “D.D.,” and the crest of the House of Devonshire – a serpent rampant.

The oak and elm trees were outlined with green lamps, while the avenues to the east and west were festooned with variegated lamps of pearl and green. Japanese lanterns were hung upon the trees, and the flower beds along the north front of the hose were outlined in fairy lamps of red, white, and blue. Coloured fires were burned at intervals, and with twelve thousand lamps, made a brilliant illumination.”

From the enormous amount written in newspapers following the Ball and the fact that different publications describe costumes in some cases in identical wording, it is obvious that many of the guests or their costumiers made available detailed costume descriptions and possibly sketches of the costumes in order that they could be reported correctly and with all their pertinent details. In their eagerness to report on the Ball, many newspapers, in their following day's edition, also carried line drawings of the guests in costume and images from the ball would be published over the coming months in a variety of illustrated magazines. One of the Duke's biographers, Henry Leach, summed up the effect of the evening's celebrations: "It seemed too beautiful to be real, and too much superior to anything that the generation had seen before in London. When the sun rose in the morning as the signal to depart, it was as if the Duchess of Devonshire had worked a spell upon the gathering, and that they had enjoyed no other than the intangible delights of a midsummer night's dream."

The published album of guests in costume

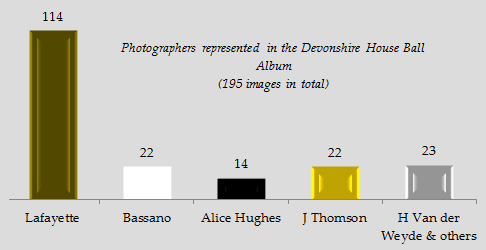

The knowledge that an album would be published with portraits of the guests in costume may well have led those who were not satisfied with the results of the hurried photographic session at the Ball to visit the Lafayette studio once or twice more with their costumes – some people up to six months after the event. The record of the event was finally published privately in 1899 with 286 sepia photogravure reproductions by Walker & Boutall and contains 114 plates by Lafayette, 22 by Bassano, 14 by Alice Hughes, 22 by J Thomson, 23 by Henry Van der Weyde and others. The Lafayette archive at the V&A contains the only known surviving negatives by any photographer from the occasion.

|

This photographic record of a stately masquerade for the enjoyment and admiration of posterity was mirrored six years later at the Romanov costume ball held in the Winter Palace where the guests were restricted to wearing only historic Russian costume. Although the Romanov ball was glamorous, sumptuous and visually impressive it was undeniably Russo-centric and some of the guests appeared a little frayed around the edges. The Devonshire House Ball was less parochial and more of a fantasy evening where an ancient Mesopotamian empress might have been found chatting lending an ear to Admiral Nelson, where Cleopatra gossiped with Cleopatra or where Mary Queen of Scots could be seen sharing a joke with Queen Elizabeth I.

Some of the ladies at the Ball, dressed as Semiramis, Salammbô, Delilah or Zenobia, could only truly be identified as such after their alter egos had been announced upon the presentation of the quadrilles. The point of dressing up as a historical character is to be instantly recognizable and perhaps to choose to impersonate Cleopatra, one should choose a form of costume that is the most likely to be already imprinted in the viewer's mind as the most characteristic. Mrs Paget's Cleopatra, even more than Lady de Grey's impersonation, was the most successful of the group of oriental costumes due to the choice of the most obvious attributes incorporated by the costumier. As far back as 1711, the Spectator had pointed out the transience of portraits of sitters in contemporary costume – as tastes and fashions changed so rapidly, and still do, a portrait might be considered to have 'lapsed into unfashionability' within a decade. The corollary of this argument is that a portrait in historical costume achieves an aura of timelessness.

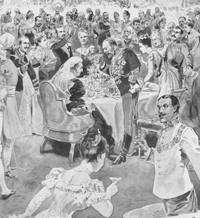

The arrival of the royal party, as depicted by The Illustrated London News, 10 July 1897 |

The images finally chosen for inclusion in the album give a sense of the private lives of the cream of the upper 10,000, as the somewhat random number of people who made up Society were referred to. The images depict the ruling classes, be they royalty, aristocracy or simply the controllers of immense personal wealth, as the pinnacle of the social hierarchy, as superior people whose taste, deportment, manners and behaviour were something to be looked up to, and who served as an example, in the new age of the illustrated press, to be looked up to by the respectable middle classes but who knows, also to be sneered at by those discontented with the prevailing and rigid social order. The aristocracy, in particular, craved good press, as a hint or murmur of anything untoward about them appearing in print, just as in the age of google, could be their undoing or land an indelible blotch on their reputation

Appearing in, and possessing, the Devonshire House Ball Album indicated that the guest was in a position to have participated in one the greatest, most expensive, and carefully planned episodes of extravagant whimsy. Many were the members of the aristocracy who, short of funds to maintain their grandiose and enormous stately homes, had already for decades been rushing around to find and marry American heiresses who gained a title and saved an estate Lady Randolph Churchill being perhaps the best known to posterity, but little would the guests have thought, at the time, that within most of their lifetimes society would emerge transformed from the monstrous carnage of the Great War, and that Britain's historic links, and the royal family's familial ties, to Germany, would be severed. Britain's Hanoverian hinterland, and the pool of eligible Protestant princes and princess from a great number of German states which were its marriage reservoir would be no more. Great Britain would see its ruling family Anglicise their name from Saxe Coburg and Gotha to Windsor. Many aristocrats, even those who retained their fortunes, would no longer see fit to live the sometimes vapid and leisure- and pleasure-seeking late Victorian way of life, so dependent upon armies of servants.

The album itself, measuring 33 cm x 25 cm and entitled simply Diamond Jubilee Fancy Dress Ball, is an extreme example of a sub-culture in-joke. It was never intended to be seen the general public, and contains no more clue to what is going on inside the covers than its title, a list of those who must have been instrumental in choosing whom to include and who then presented the album to the Duchess of Devonshire and the names of the people whose portraits in costume are reproduced in the album. The plates in the album were prepared for photogravure by Walker & Boutall (Sir Emery Walker & Walter Boutall), and the album 'Committee' acknowledged "the courtesy of the photographers, whose names are engraved below the portraits, in lending the negatives from which these plates have been made."

The commission from the Duchess of Devonshire to photograph the Ball would have brought enormous publicity value to the firm of Lafayette who opened their first London studio in 1897 to capitalise on the capital's commercial bulge during the jubilee year. Indeed, contact sheets found in display albums from the London studio show that the firm's regular customers could order prints of the Ball's guests in costume. Only some very few original prints from the Ball are known to exist.

Demolition

In 1924, almost three hundred years after it was built, Devonshire House was demolished to make way for an office block, whose ground floor is now occupied by Marks & Spencer and the Green Park Tube station. The London landmark's disappearance was mourned in the illustrated press, which printed a series of photographs of a building site, and the palace itself passed into existence only in literature, such as the 1933 novel Pluie d'étoiles by Matila Ghyka:

"Je ne me suis pas encore habitué à la disparition de Devonshire House. C'est presqu'un crime et cela m'offusque plus que si on avait rasé Saint-Paul, ou le Stock Exchange."

Only the magnificent wrought iron gates of the house (installed post 1897) survived complete with their sphinx-topped Greek revival piers, relocated to the edge of Green Park on the opposite side of Piccadilly where they can still be seen.

| List of Sitters |

| All text copyright © Russell Harris 2011 |

|

Illustration of a "commemorative medal of the sexagenary of Her Majesty's reign" prepared by Messers. Spink & Son.

Illustration of a "commemorative medal of the sexagenary of Her Majesty's reign" prepared by Messers. Spink & Son.

Illustration from The Queen: The Lady's Newspaper

Click on image to enlarge

Devonshire House on John Rocque's 1746 map of London

Devonshire House on John Rocque's 1746 map of London

Click on image to enlarge Devonshire House, Piccadilly, c 1895

Devonshire House, Piccadilly, c 1895

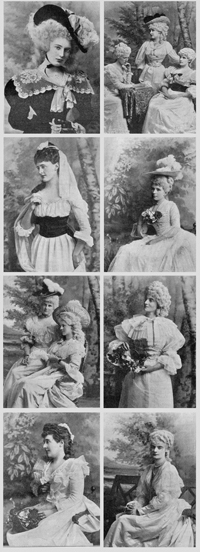

Lady Wolseley's Costume Ball at the Royal Hospital Dublin. Fancy dress gave Society ladies an opportunity to exaggerate their Victorian femininity, to explore the fantasy realms of Romney and Reynolds and knowingly to draw attention to their own offered delights. Portraits by Lafayette of society beauties in costume as published in the Illustrated London News on 23 March 1893

Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee Dinner Party at Buckingham Palace, 21 June 1897: "The Prince of Wales Proposing the Toast of Her Majesty's Health" (Detail of drawing by T. Walter Wilson, in Sir Richard Holmes, Edward VII: His Life and Times, London, 1911, p 411)

Title page of the privately published Album of guests at the Ball

The Czar and Czarina of Russia in Old Court Dress of the Time of Peter the Great as they appeared at the costume ball of February 1903.

The Czar and Czarina of Russia in Old Court Dress of the Time of Peter the Great as they appeared at the costume ball of February 1903.

Click on image to enlarge

The Great Georgian Ball given by the Duchess of Albany on 14 April 1920 was the last social function to take place in Devonshire House on Piccadilly. By 1920 the music played at Devonshire House was a little racier, and reports stated that "couples were seen doing the fox-trot!"

The couple seen here, General Blue and Miss Sanger, are possibly part of a group of guests from the United States embassy. General Blue wears 18th-century velvet court dress (old style).

Click on image to enlarge

Devonshire House, Piccadilly, 2003, now an office building with a branch of Marks & Spencer and a tube entrance at ground floor level