Introduction and background to the Lafayette studio

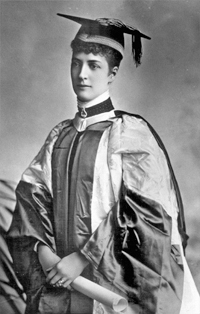

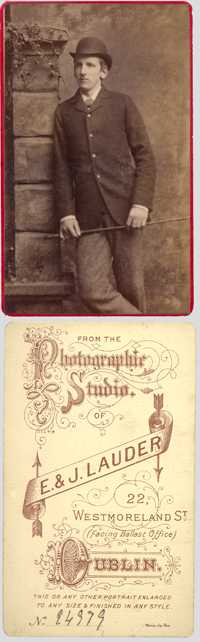

Studio Beginnings The Lafayette studio has one of the oldest histories of any photographic business in the world. During its peak years, the studio photographed a succession of Queen Empresses, King Emperors, Viceroys and Vicereines, royalties domestic and foreign, top colonial administrators, luminaries of the stage, great figures in the Church, Irish revolutionaries, debutantes, society ladies, prize race horses, military men, genre scenes and even the odd building, such as Sandringham House and Glamis Castle. Lafayette was founded in Dublin in 1880 by James Stack Lauder, who used the professional name of James Lafayette ("late of Paris", as his own firm's publicity billed him). James was the eldest son of Edmund Lauder, a pioneering and successful photographer who had opened a daguerreotype studio in Dublin in 1853. In adopting the name "Lafayette", James created a new image for the family business, seeking to prosper from the cachet of a French name: Paris was then the centre of the art world and of avant-garde photography in particular. The carte de visite (seen here front and back) of an unknown young gentleman from the photographic studio of E & J Lauder in Dublin are run of the mill portraits which were a great success in the early days of commercial photography. They were produced by the millions as portraiture was now affordable by almost everyone and no longer the preserve of the well-heeled and refined sector of society. James Lafayette was 27 when he founded the new firm which, in its early days, was variously known as 'Jacques Lafayette', 'J. Lafayette' and 'Lafayette' – sometimes with the additional wording ‘Late of Paris’. In fact, he was joined in the new venture by his three brothers, all of whom were experienced photographers who had worked in their father's three studios. The studio had gone from a standard Daguerreotype studio, to producing the highly fashionable cartes de visite and by the 1880s the studio’s output was praised in print by the Photographic Society of Great Britain as “very beautiful, being distinguished for delicacy of treatment...” and his early experiments with hand-colouring produced images which were described as “permanent carbon photographs painted in water-colour on porcelain.” Lafayette’s photographic entries in the numerous industrial exhibitions and competitions of the day won medal after medal and the new specialist photographic press waxed generally lyrical over the fine quality of Monsieur Lafayette’s portraiture. In examining the work which won a gold medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889, his output was noted to be of the highest technical excellence. His poses were graceful and good, the flesh was rendered as flesh and the folds of the drapery were rich and effective in the “Rembrandt style". The reviewer mentions that the showiness of some of the backdrops might offend some and that the plainer proved that his work stood on its own. Royal connectionsLafayette’s reputation was such that in 1884 “J Lafayette alias J.S. Lauder” of 30 Westmoreland St Dublin, was elected a Member of the Photographic Society of Great Britain, the following year he was receiving favourable reviews in The Times for his portraits of the Prince and Princess of Wales and in 1887 he was invited to Windsor to photograph Queen Victoria. The crowning honour, however, in his artistic and commercial career was the summons he received from Her Majesty the Queen, at whose command he proceeded to Windsor and photographed the Royal family; the distinguished honour permitted him to sign himself "Photographer to Her Majesty at Dublin” by special warrant granted on 6 March 1887. As a firm specialising in portraiture the warrant was probably the credential that mattered most although constant efforts were required maintain and increase the value of the brand name. For this the warrant was of particular value. It acted as a magnet for an increased clientele whose choice of photographer was often guided by the choice of other people, in particular the social status of the studio’s sitters as well as quality and number of celebrity sitters. Lafayette told of this commission in an 1898 interview: “I commenced in Dublin about fifteen years ago, and rapidly came into favour with the Viceregal Court. The aristocracy followed suit, and I had not been established more than two or three years before the Princess of Wales visited Ireland, and during that visit the degree of Mus. Doc. was conferred upon her. I was sent for to photograph her Royal Highness in Academic robes and mortar-board, and that photograph was sent all over the world, having, I believe, the largest sale of any photograph ever published.” It was claimed that this image, reproduced as a postcard, sold over eighty thousand copies by 1900. It was also the very first photograph registered by the firm of Lafayette for copyright at Stationers’ Hall in London. |

The Victorian actor George Grossmith Jr. sang in an 1881 song "with imitation banjo accompaniment" of a lady whose heart was so broken by a photographer that: She said, Then she swallowed

When registering this pose for copyright at Stationer's Hall, the photograph was carefully described as "Photograph of Her Royal Highness The Princess of Wales in Robes of Dr of Music ¾ face"

|

||

Basking in the glamour of the Princess of WalesHaving a photogenic princess of Wales who agreed to sit for Monsieur Lafayette also helped the company’s fortunes. An image of Alexandra in the robes of a doctor of music was issued as a postcard. The princess had long been considered a great beauty and an ideal figure of motherhood and the conferral upon her of an honorary doctorate by the Royal University of Ireland during the royal visit in 1885 set her star high in the popular constellation. “A compliment is paid to photography in the statue of the Princess of Wales, by Prince Victor Hohenlohe, recently on view at St. James Palace,” stated the Photographic News in 1891. “The statue is almost a literal reproduction of the admirable portrait of the Princess taken by Mr. Lafayette, of Dublin, and representing her in the doctor's cap and university gown. The photograph, it is well known, has influenced fashion - not the only photograph, by the way, which has had this effect...” This Royal Warrant, which was subsequently renewed by King Edward VII and George V, conferred enormous prestige. The style and title of ‘Photographer Royal’, which now appeared on the studio advertising and promotional literature, proved extremely useful in attracting new clients. The business expanded rapidly in the 1890s. Studios were established in Glasgow (1890), Manchester (1892, and with the expected business bulge in Jubilee year (1897) a branch was opened on London’s fashionable Bond Street. Subsequently another studio was established in Belfast (1900). In 1898 all the Lauder family businesses were incorporated and shares in the newly established The studio on London’s Bond StreetLondon’s Bond Street was almost a Mecca for photographer’s studios, located in the heart of Mayfair and a stone’s throw from Buckingham Palace, the street was strategic both for those aristocrats who had London residences nearby, the grand foreigners in London on shopping forays or to be decorated at the palace, and the hordes of debutantes and guests summoned to levees and drawing rooms who would naturally wish to record themselves at their finest moments of prestige and finery of raiment. Street directories of 1897 show only four other photographic firms on Bond Street (Franz Baum, Bassano, Arthur Esme Collins and The Photograph Co.), although by 1914 Lafayette was competing with fifteen other firms on Bond Street alone. The studio in London, along with its patent fog-clearing equipment was particularly convenient for debutantes, who had just been presented at the palace and wished to be memorialised wearing their very complicated and cumbersome court dress. It was no easy matter for them to walk the three flights of stairs to the top floor studio, under the glass skylight, which was where all photographic studios needed to be situated in the days before electric light, and dull skies and lack of light was the greatest enemy of photographic establishments, as it could render a whole day unsuitable for portrait-making: “‘My finest establishment,’ [Mr. Lafayette] said to me when he was explaining his conquest of the fog demon, ‘is at Glasgow. I put it [the fog-clearing electric reflector] there because Glasgow is one of the foggiest cities in the three kingdoms. I have beaten the fog there, and I am coming to London to do the same with the thickest variety of atmospheric pea-soup that you can find me…’ And then, for about the twentieth time, I put the question: “’How do you do it?’ ‘It’s very simple; not altogether original, but an adaptation of a device invented by a German engineer. You see, the atmosphere is a sort of sponge; it takes up a lot of moisture. this moisture holds particles of free carbon, dust, and other opaque substances, and the reason why the electric light is no use in fog is that the sides of these particles break up the rays, and reflect them in all directions. The result is not a light, but only an illuminated fog. Now, if you can keep the fog out of your studio, and dry the air inside it, those solid bodies will be precipitated in the form of dust, and your fog will vanish. Do you see?’” In the studio’s commercial portraits, Lafayette followed a well-tested recipe. As with the early days of the daguerreotype in the 1840s when having an image made of oneself suddenly became affordable and no longer the preserve of active patrons of painters, the subjects of portraits became, as many historians have pointed out, democratised. In other words, the commercial photographer faced the situation of having to make flattering photographs of people with no experience of sitting for a portrait. The exceptions to this were generally the actors and actresses, including Lillie Langtry and Sarah Bernhardt, who sat for Lafayette and whose finished portraits show an acute consciousness of pose and gaze. Royalties were adept at adopting and holding an expressionless mien and understanding the expertise of the portrait photographer, as they also knew that every image captured in the studio would most probably be reproduced far and wide and examined by all posterity. However it is clear that as well as producing portraits pleasing to this sitters, part of Lafayette’s business success can be ascribed to the fact that he made cleverly slipped into the order of the day for those summoned to court a visit to the Lafayette studio, just after having been to the palace and before rushing home to change for a debutante’s ball. The photographer was at the mercy of his subject to a greater degree than the portrait painter, as he could not so seamlessly add to the sitter any missing, but standard, attributes of a courtly figure. Cecil Beaton’s description of a daguerreotype studio could be applied throughout the carte-de-visite vogue and can also be seen in many portraits from the Lafayette archive up to 1914, even of sitters whose august presence had no need to be further amplified: “In an attempt, however, to invest his sitters with a little reflected glamour, the photographer surrounded them with all the appurtenances of culture and wealth. Studios were rigged up with balustrades, palms, books and potted flowers, to suggested an exalted social rank and elegant surroundings.” |

|||

The rise of the illustrated press Lafayette's commercial was helped by developments in the half-tone printing process which resulted in the proliferation of illustrated weekly magazines and a reduction in the costs involved in publishing photographs. The firm was one of the first to recognize the opportunities offered by syndicating photographs, as stated in blunt terms by The Photogram in 1890 "The most profitable new field now lying open to photographers is in the supply of matter for reproduction in the illustrated press". Reasons for this were the increasing number of new illustrated titles appearing, the fact that books could also now be illustrated with photographs – or at the very least a photographic portrait of the author as the frontispiece, the photograph could offer new material for the publisher, and finally editors were starting to choose their photographic illustrations with a more discerning approach than previously and hence were in need of a greater supply of images from bespoke and respected firms. The Queen, The Tatler, Chic, Madame, Cycling World, Country Life, Car Illustrated, Candid Friend, and The Throne, inter alia, regularly carried full page photographs of beautiful society ladies by Lafayette – one of his favourite and easiest subjects to capture, as he himself put it: "Well, some of the great ladies of the land are perfect as sitters." The illustrated press gave great prominence to beautiful society women, regularly devoting whole pages to their images showing them in various vignettes and poses which set them up as almost high priestesses of the Victorian quasi-religion of femininity-worship. Indeed, a well-placed article in The Lady’s Realm in 1900 stated outright: “It is well-night impossible to open any magazine or paper which contains portraits of present-day celebrities without seeing at least one reproduction of a photograph by the well-known Lafayette house.” The article even claimed that the photographs could generally be distinguished from others, due to “the special Lafayette silver process.” However, it was not always plain sailing, and as far back as 1879 the editor of Town Talk launched an attack on the implied immorality in the phenomenon of society beauties:

The studio sold images to the press in huge numbers, and The Car, for example, was carrying in 1903 an average of three Lafayette images per week. The male of the species also had his place and portraits of distinguished men and from society and the stage appeared prominently in the various new publications and of course recent purchasers of the supremely elegant new automobiles, were wont to be photographed with their prize horse-power vehicle. Of its very nature, a studio frequented some of the grandest, and most staid, people in the country did not have a pioneering aspect in its commercial work. The Lafayette recipe for a studio portrait was obviously not one to be tampered or tinkered with – and this is clear from the work produced by the studio up until the end of World War I. Aside from ringing the changes in ladies’ costumes, which were essentially minor and more modifications of the various accessories than a re-shaping of the female figure, the studio’s output until 1919 is of a static quality and even the change of backdrops had more to do with a client’s choice than with the studio actively attempting to “update” its style of portraiture. However, the studio, like many other photographic establishments, offered various optional extras, such a hand-colouring in pastels, painting on porcelain. The painted lettering on the door leading to the offices of the London studio read “Photographers and Portrait Painters,” and the firm’s stationery stated “photographs enlarged to life-size & painted in oils or water colors [sic]”. “It has been Mr. Lafayette’s blissful lot to photograph more of the most beautiful and distinguished women of Europe than anyone else,” wrote Levin Carnac (pseudonym of the author George Chetwynd Griffith-Jones) in Pearson’s Magazine in 1897. Published series of “Society Beauties” show, the same writer stated at the zenith of Lafayette’s abilities, that “photography is one of the most exquisite and delicate of the fine arts, and… a large share of the credit of this development belongs to the artist whose classic French name is familiar wherever photography at its best is known.” |

|

||

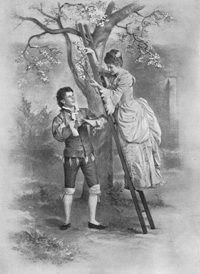

A certain archaic styleIn keeping with a certain pedestrian attitude towards advances in artistic photography, the studio kept on producing high Victorian genre scenes until remarkably late. In August 1888 The Photographic News had called two of Lafayette’s genre pictures “perfect specimens of the photographic art”. Blossoming Hopes, reproduced in The Illustrated London News in 1895 as a full page plate, is one of an enormous series of artificial scenes registered for copyright and reproduced either as postcards or full page illustrations in the press. As well as producing a number of faux rustic tableaux of mother and child, the studio also registered many idylls for copyright. The subjects are generally posed in faux Mozartian scenes overlaid with innuendo in a style which might be termed programmatic photography, ‘Blossoming Hopes’, was registered for copyright on 6 June 1894 with the photographer’s description “group of two figures, girl on ladder gathering apple blossom, man under tree receiving same in his hat.” These secret of the much vaunted “Bartolozzi crayon drawing”, was revealed, amid much praise, by The Lady’s Realm in 1900: “The Bartolozzi crayon drawings... are in reality carbon photographs, but if exhibited side by side with crayon drawings it would be difficult for even a connoisseur to distinguish the difference. Photographs similar to these are used for book illustrations and engravings; and looking at some of these, one would almost imagine they were Watteaus. In many cases they are half-photographs and half-drawings - that is to say, a photograph is taken of two or three figures and perhaps a little scenery, and then some more background is painted in making such a harmonious whole that no appreciable difference can be seen.” The fad for these illustrative tableaux appears to have peaked in around 1895 and the poses could include a slight amount of titillation – in one such image two ladies, tightly corseted in their beribboned bathing suits, heavily bestockinged legs, slashed sleeves and bonnets, are posed gingerly stepping down from a bathing hut into a painted backdrop of wavelets breaking gently at their feet. This particular study was registered for copyright in August 1895 under the title “A little bit afraid.” It could well have been this over-fussy characterisation to which the judges at the Leytonstone Camera Club referred in December 1895. While awarding Mr G Lafayette a gold medal, they also commented about one of his less winning exhibits and expressed the hope that he “would do well to refrain from exhibiting that example of the worst kind of artificiality that photography has lent itself to in the past.” This did not stop the photographer, and on 23 March 1896, the copyright records show a photograph with the enlightening description “Photograph of a Baby in a jar, feeding bottle held in right hand., termed "Baby in Jar". |

|

||

A paucity of negativesThe archives of the studio show in some cases a sequence of shots from which just one or two might be chosen for printing-up and publication. In 1924 the photographer Cecil Beaton needed over 70 shots in order to produce a couple of heart-stopping portraits of Princess Dürrüshehvar of Berar, daughter of the last Caliph of Islam, whose “…aquiline nose, the pointed, pouting lips, the large, lean cheekbones and fierce bird-like eyes, were enormously impressive in the manner of primitive sculpture.” Monsieur Lafayette could achieve brilliant results from just four of five poses. An 1898 interview with the master himself explains why there are so few negatives from a session: “Well, my art consists in recognising that photography represents indiscriminately the defects as well as the beauties in the subject. Consequently selection becomes necessary, and thus by mechanical and other means tshe camera is made to act more intelligently in the hands of a skilled operator. It is perfectly practicable to keep out of focus and render subservient those parts of your subject which an artist with feeling would, in painting, treat in a similar way.” Lafayette’s technique is borne out through a study of the negatives of almost any sitter from a photographic session, where the three or four different poses or attitudes are almost always successful. An examination of the whole archive held by the V&A can produce only a very small number of unsuccessful images, and these are generally of debutantes, whose shyness or resentment at being stuffed into an unwieldy costume sometimes shows through. To these one might add a small number of older ladies presented at court with their mutton-like figures stuffed into lamb-like outfits. Although there is no documentary proof, it is surmised that the studio stored the negatives which they deemed to be of commercial value – possibly for intended sale to the illustrated press whenever one of the subjects was in the news, or passed away, as obituaries often appeared with a portrait of the deceased. Over the years this storeroom of negatives became the press archive of the studio. However, when the London branch of Lafayette closed in 1952, these boxes of negatives were simply abandoned in a Fleet Street attic. The Dublin branch of the studio also kept a number of negatives on the premises, and these, numbering some few hundred, were acquired in the 2000s by the robe makers Ede & Ravenscroft. The Dublin negatives contain some significant images of personalities connected with the Irish struggle for independence, and to the modern scholar it appears slightly incongruous that the same photographic firm could be photographing the king and queen in London at same time as they were making portraits of the Irish revolutionary leaders Michael Collins and Eamon de Valera in Dublin. The boxes of negatives stashed away in Fleet Street were not rediscovered until 1991 when the building was about to be demolished. As The Times reported: “The workmen wore thick overalls and gloves to clear the jumble of glass and cardboard boxes piled high in a London attic. Their instructions were to throw away everything and redecorate. However, Terry Thurston, the foreman, took a second look at the "rubbish" buried beneath a thick layer of dust, cobwebs and broken glass, and knew he couldn't throw out the thousands of glass negatives scattered everywhere. But for his alertness, history would have ended up in a skip. Although he did not know it, Thurston had saved for the nation one of the largest and most important collections of 19th and early 20th century portrait photographs.” The extant archive held by the Victoria & Albert Museum covers the period 1885-1933 and contains images ranging from Emperor William II of Germany, Prince Nicolas of Romania, Queen Elizabeth the late Queen Mother, the great Abyssinian general Ras Makönnen, Malay Sultans, Earls, Marchionesses, Prime Ministers and colonial administrators, peers and peeresses in their robes, diplomats, debutantes and other court attendees, as well as professional men, a sizeable proportion of the maharajas and maharanis of important salute states in India, actors and actresses as well as early film stars. Registration of photographs for copyright started in 1862 and continued until 1912, and photographers successful and amateur zealously filled out a form for any photograph they deemed to have worth and filed this form, upon payment of sixpence [2.5 pence] in most cases along with a copy of the photograph itself. Approximately 55,000 photographic portraits were identified in the Stationers’ Hall archive and their details, such as the name and address of the photographer, the verbatim description of the photograph written by the photographer on the form and the date of registration were all transcribed into a database. The task of identifying the given names on the copyright forms with the last given name of the sitters was carried out by this author – a huge undertaking, most particularly since royal and aristocratic personages underwent many changes of name during the course of their lives and standard practise is to list a sitter by their name at time of death. Jennie Jerome is a case in point. At marriage she became Lady Randolph Churchill, then Mrs. George Cornwallis-West, then Mrs Montagu Phippen Porch. The resulting database has proved invaluable in tracing the output of both individual photographers and the changing guise in which particular sitters were photographed. 539 images by James Stack Lauder and the firm of Lafayette have been identified, ranging from studies or genre scenes to portraits of Queen Victoria. Certain statistics extracted from this database help to paint a picture of the age and its visual delights. King Edward VII appears in 957 of the c. 55,000 portraits registered for copyright, followed by Queen Alexandra with 829 images by over 180 photographers, but the general picture given by this archive is of a not too different age from our own, where the predominant imagery considered important enough to be protected by copyright was that of royalty and celebrities of the stage who together represented over 95% of the top 100 personalities in the archive. The Lafayette archive, of approximately 3,500 glass plate negatives and tens of thousands of later nitrate negatives, dates from 1885 to the early 1930s does not represent the complete output of the Lafayette studio, as research into the Stationer's Hall archive and the illustrated press proves that, particularly in the pre-WWI period the clientele photographed by the studio included many more people than those in the archive. Research into the illustrated press throws up hundreds of published portraits such as that of the Countess of Limerick from March 1897. For many of the sitters in the archive, there are numerous images published for which the negatives no longer exist. The largest number of negatives connected with one specific event are those of the guests in costume at the Devonshire House Ball. |

Reproduced from JA Hammerton, ed, Our King and Queen, London, 1935 |

||

|

|||

|

Unknown sitter, 1880s

Unknown sitter, 1880s